Hydropower is the cleanest and perhaps the cheapest form of electricity. Large hydropower projects even have cascading social benefits like facilities like irrigation and drinking water supply. However, construction of large hydropower projects has never been an easy task considering the concomitant geographical, financial and social implications. Despite all odds, hydropower generation is expected to be a major source of new power generation capacity beginning from the XII Plan period, writes Venugopal Pillai.

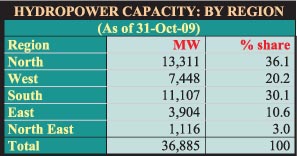

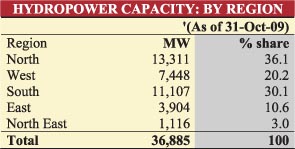

India has a long history in building hydropower plants with its first project commissioning way back in 1898. Despite the century-old experience, inadequacy is very evident. Today, the country's hydropower capacity is barely 37,000 mw, accounting for less than a quarter of the total capacity. In the race of capacity addition, hydropower has lost out to thermal power (mainly coal-based), which clocked nearly 1 lakh mw of cumulative installed capacity as of October 2009. India has a long history in building hydropower plants with its first project commissioning way back in 1898. Despite the century-old experience, inadequacy is very evident. Today, the country's hydropower capacity is barely 37,000 mw, accounting for less than a quarter of the total capacity. In the race of capacity addition, hydropower has lost out to thermal power (mainly coal-based), which clocked nearly 1 lakh mw of cumulative installed capacity as of October 2009.

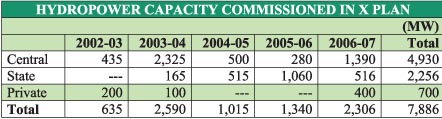

India's seriousness in developing large hydropower projects re-emerged only in the X Plan (2002-07) and as things stand today, a revival of hydropower projects is very much on the cards during the XI and XII Plan period. What is even more inspiring is that new capacity addition would come from a combination of forces—public, private, PPPs and even partnerships between Central and state government agencies.

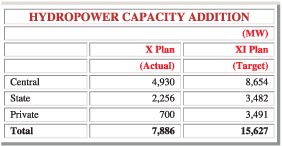

In the X Plan period, the country saw addition of 7,886 mw of hydropower capacity from large schemes (capacity exceeding 25 mw). Although this was nowhere near the targeted 14,393 mw, that Plan period took the credit of being the best ever in terms of actual addition. In fact, hydropower accounted for a very respectable 37 per cent of the total 21,180 mw of new capacity added during the period. As of March 31, 2007, the end of the X Plan period, India's hydropower capacity stood at around 33,486 mw, nearly a quarter of which was added in that Plan period alone.

|

Worsening hydro-thermal mix

Over the years, India's capacity addition has largely been from thermal power projects-mainly coal-fired plants. This has no doubt propelled energy availability but, in the process, has worsened the optimal hydro-thermal mix. For India, the optimum hydro-thermal mix is 40:60, which means that at a given time point, out of the total power capacity installed, around 40 per cent should come from hydropower projects (clean energy) while 60 per cent could be thermal. Though India has endeavoured to add hydropower capacity, the pace has fallen short of expectations, with large hydropower projects easily succumbing to environment-related resistance, topographic challenges and  a plethora of other hindrances. a plethora of other hindrances.

Way back in 1966, hydropower capacity accounted for a very healthy 46 per cent of total capacity but this slipped to 41 per cent by 1979-however, still conforming to the optimal ratio. Beginning from the 1980s, hydropower capacity addition decelerated and could not match the vigorous addition from coal-fired plants. By 1990, hydropower accounted for 29 per cent of total power capacity-a metric that gradually worsened to 25 per cent by 2002 and further to 24 per cent as of October this year. On the brighter side though, one must note here that slow addition of hydropower capacity from large plants, has been offset by notable progress made by small hydropower projects and also by other forms of clean energy like wind. Till the 1990s, the only conventional form of clean energy known was large hydropower projects, till renewable and non-conventional energy sources like small hydropower, biomass, wind, etc, came into the picture.

Apart from being a clean source of energy, hydropower projects play a critical role in peak load power management. Thermal power projects operate continuously while hydropower units can be "shut off", and restarted instantly. Thus, while thermal power projects are designed to meet the base load requirement, hydropower projects, due to their "instantaneous" nature of operations come into play to meet the peak load demand. The poor pace of hydropower capacity addition has to some extent affected the country's peak power demand equation. |

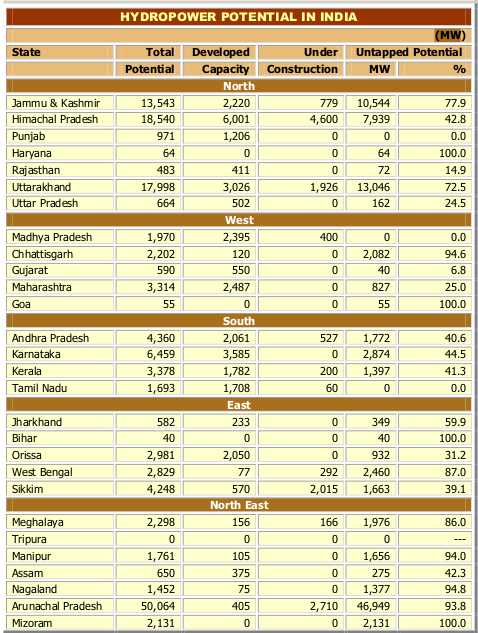

Hydropower, in principle, represents a vastly untapped energy resource. Central Electricity Authority has estimated that of the total potential of 1,45,320 mw coming from large (more than 25 mw) schemes alone, only 22.1 per cent has transmuted into installed capacity. With another 9.4 per cent under construction, the untapped potential is a huge 68.50 per cent standing for nearly 1 lakh mw. Arunachal Pradesh is the hydropower capital when it comes to potential—50,064 mw or 34 per cent of India's total. However, when it comes to potential unexploited, it is a towering 94 per cent. Tapping India's vast hydropower potential is a formidable task as over half of it lies in the north eastern region where difficult geography is infamous for frustrating project progress.

The ongoing XI Plan period has seen some early success but apprehensions remain about the fulfillment of the target. New hydropower capacity of 15,627 mw is targeted to come on stream in the ongoing Plan period and as of October 31, 2009, actual addition was 3,431 mw. This means that at just a little more than the halfway mark, the target attainment was around 22 per cent. Much of the capacity that has been commissioned in this Plan period is indeed a carry-forward of the previous Plan's target. The 900-mw Purulia pumped storage power plant in West Bengal is a prime example. Other schemes to have turned operational in this Plan period included Teesta-V (510 mw, Sikkim), Omkareshwar (520 mw, Madhya Pradesh) and Baglihar (450 mw, Jammu & Kashmir).

|

Tackling social resistance

NTPC very recently got an insurance cover for an entire village against for five years any mishap while carrying out work on its 520-mw Tapovan Vishnugad project in Chamoli district of Uttarakhand.

This is a very significant development and as industry experts see, could set a precedent for other large hydropower projects in the making—both by public and private sector enterprises. Hydropower projects are known to be overwhelmed by social resistance and such a move could create much confidence amongst the people living in the project vicinity. Ultimately, this move could expedite project implementation and in a very positive way, experts feel.

NTPC has spent Rs.8.26 crore on the insurance cover for a period of five years, and may consider extending it if need be. As such, the insurance covers accounts for only a fraction of the total project cost of Rs.3,000 crore but is poised to speed up the implementation process greatly. The insurance policy covers the 100-odd families of Selang village, which is close to the project site. In all, 164 structures are covered under the policy, which includes houses and even cow-sheds of the villagers, along with the Panchayat Bhavan, the local school and a temple. NTPC has spent Rs.8.26 crore on the insurance cover for a period of five years, and may consider extending it if need be. As such, the insurance covers accounts for only a fraction of the total project cost of Rs.3,000 crore but is poised to speed up the implementation process greatly. The insurance policy covers the 100-odd families of Selang village, which is close to the project site. In all, 164 structures are covered under the policy, which includes houses and even cow-sheds of the villagers, along with the Panchayat Bhavan, the local school and a temple.

This innovative and truly path-breaking step comes from thermal power-centric NTPC for whom hydropower is only a recent diversification plan. NTPC, with no operational hydropower capacity, has planned to add over 2,300-mw from this clean source in Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh. In most likelihood, the 520-mw Vishnugad Tapovan project could be NTPC's first hydropower commissioning, given that other projects like Koldam (800 mw, Himachal Pradesh) and Loharinag Pala (600 mw, Uttarakhand) are facing delays related to topography and environment-related opposition, respectively. |

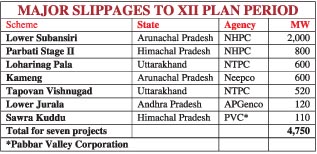

Of the total 15,627 mw targeted to commission in the XI Plan, seven projects aggregating 4,750 mw (or 30 per cent of the total) are scheduled for completion in the terminal year (2011-12), going by original targets. The XI Plan's overall success is thus critical on these projects. The biggest in these is the massive 2,000-mw Lower Subansiri project of NHPC in Arunachal Pradesh. This project is significant as it would be India's biggest hydropower project thus far and would be an important forerunner in realizing Arunachal's hydropower aspirations.

The ground reality is rather disturbing—each of these seven projects is contending with difficulties and commissioning with the XI Plan period appears as only a remote possibility. For instance, the 2,000-mw Subansiri project is now facing a law and order problem, adding to a host of problems that included the washing away of the coffer dam in 2008. Flash floods last year took a toll on the 600-mw Kameng project in Arunachal Pradesh and more recently, the Lower Jurala project in Andhra Pradesh faced the same fate. NTPC's projects in Uttarakhand—Tapovan Vishnugad (520 mw) and Loharinag Pala (600 mw)—are facing delays arising out of geological concerns or social resistance.

Going by the current trends, it is likely that new hydropower capacity worth 6,916 mw is likely to materialize during the remaining part of the XI Plan period. Including the 3,431 mw already commissioned up to October 2009, the total addition in the best case could be 10,347 mw implying target achievement of 66 per cent.

Gearing up for XII Plan

Building large hydropower projects is always a challenging task. In the Indian context, it takes up to ten years to build a large scheme—from concept to commissioning. The construction period alone is five years on average. Thus, while hydropower projects offer the cleanest source of energy, several  challenges need to be surpassed before these assets can be put in operation. Apart from surprises and shocks during the construction phase, hydropower projects are also known to face delays in the drawing board and clearance stage. While one must accept that India's hydropower scenario has been improving in terms of new capacity added, the pace needs be accelerated. In the XII Plan period, hydropower capacity of around 30,000 mw is slated for addition, which is almost twice the target in the ongoing XI Plan period. Keeping this in mind, Central Electricity Authority in 2006-07 embarked on an advance action plan, identifying a shelf of projects aggregating 58,573 mw. This would form the basis of the XII Plan capacity addition, and to some extent, would compensate for delayed commissioning of originally-conceived projects. challenges need to be surpassed before these assets can be put in operation. Apart from surprises and shocks during the construction phase, hydropower projects are also known to face delays in the drawing board and clearance stage. While one must accept that India's hydropower scenario has been improving in terms of new capacity added, the pace needs be accelerated. In the XII Plan period, hydropower capacity of around 30,000 mw is slated for addition, which is almost twice the target in the ongoing XI Plan period. Keeping this in mind, Central Electricity Authority in 2006-07 embarked on an advance action plan, identifying a shelf of projects aggregating 58,573 mw. This would form the basis of the XII Plan capacity addition, and to some extent, would compensate for delayed commissioning of originally-conceived projects.

As of now, a total capacity of 25,316 mw seems feasible for addition in the XII Plan period, and another 5,604 mw subject to early completion of DPRs. This makes a total shelf of 30,920 mw. To achieve the feasible 25,316 mw, an investment of Rs.1,51,896 crore has been envisaged, with a broad equal division between Central, state and private enterprise.

CEA has recommended that 21 projects aggregating installed capacity of 5,941 mw that have already received clearance from the agency need to be taken up immediately after receiving statutory clearances and attaining financial closure. It is also important that all projects should achieve financial closure latest by September 2010, if they were to commission during the XII Plan period. CEA has also pointed out that the tendency of converting projects, approved as storage schemes, into run-of-river schemes should be avoided. The project developer should seek long term open access by indicating at least the regions in which the power generated is expected to cater to. As a recommendation, CEA has also sought that project developers should contribute to building up of skilled manpower in the project area in various trades required by the project, to promote better employment opportunities.

|

Hydropower plus

Cleanest form of energy

Best source for peak power demand

Generation cost is inflation-free

High useful life of around 50 years

Spawns socio-economic development in far-flung areas |

Private role: It is noteworthy that in the XII Plan period, the private sector is expected to play a major role in the capacity building exercise-demoting for the first time the dominance of Central government agencies. Out of the total shelf of 30,920 mw, private sector is expected to contribute 12,007 mw ahead of the Central government's 11,622 mw. State government enterprises are expected to contribute 7,291 mw—the lowest in the three broad ownership groups.

In the XI Plan, at least in terms of the targets set, the private sector is expected to commission 3,491 mw of new hydropower capacity, comparable to 3,482 mw by state government entities. Central government agencies would bring in 8,654 mw. In the X Plan (2002-07), the private sector got a toehold by commissioning 700 mw of new capacity, accounting for 9 per cent of the total. The Centre dominated with 4,930 mw of fresh addition.

As of today, the private sector owns only 3.4 per cent of the total operational hydropower capacity of 36,885 mw.

The way forward

It must be accepted that India is redoubling its efforts of developing large hydropower projects, the typical and unforeseen challenges notwithstanding. While impediments during the construction phase are inevitable, what seems to be bogging down projects is opposition by environmentalists and locals. There is perhaps not a single large hydropower project that has not faced major environment-related opposition at some stage of its execution.

It must be understood that resistance from local population is natural and inevitable, and it is an issue that needs to be handled deftly. Displacement of people will take place for any project, and hydropower schemes are no exception. Thus, project developers need to have a very inclusive approach of dealing with rehabilitation and resettlement. Even NTPC's pioneering idea of offering insurance cover to all project-affected people and their property is a very welcome move in this direction. A humane approach towards R&R is what it takes. At the same time, issues related to ecology and environment must be looked into very seriously, as flouting environment-related norms could impart irreversible damage.

It is also encouraging to note that the private sector is taking a very proactive role in shoring up India's hydropower capacity addition drive. This is commendable because setting up large hydropower is a very risky business—and certainly not the fastest means of generating returns on capital. That the private sector believes in the long-term benefits of India's hydropower growth story is very reassuring.

Talking of private sector, there is also the other extreme where some state governments have allegedly awarded hydropower projects to the private sector without detailed inquiry into the developer's credentials. This has led to no forward movement in a large number of projects in states like Himachal Pradesh, Arunachal Pradesh, Sikkim, etc. In this context, the state governments should also prepare the ground by making available detailed hydrological data to the incumbent developers. It is alleged that superficial data provided by the state government delays the preparation of the detailed project report, which has had a cascading adverse effect on the project implementation.

Regarding project implementation modes, the past few years have seen a great deal of success coming from joint ventures between Central and state governments. For instance, the country's biggest hydropower scheme—the 1,500-mw Nathpa Jhakri project—materialised only when a joint venture between the Central government and the Himachal Pradesh government was formed to implement the project. Over ten years in the making, the project was earlier to be developed by Central public sector unit NHPC. The same Centre-state model proved successful in the Tehri Dam, Sardar Sarovar and Narmada Sagar projects. While PSUs have experience in project management and implementation, the involvement of state governments helps address local issues, and is particularly helpful to quell project-related social unrest.

The biggest advantage of large hydropower projects is that they help in elevating the socio-economic conditions of the local population. It is pertinent to note that much of India's hydropower potential exists in economically backward areas—mainly the north-east. The synergy between clean energy and social uplift is striking.

If all goes well, India could add over 10,000 mw of hydropower capacity the ongoing Plan period, making it a memorable episode in its power history. In the XII Plan, one can look forward to at least 25,000 mw of capacity getting installed, and that too with significant private participation. The country now appears to be making up for precious years lost in hydropower neglect and antipathy. It looks like the country's vast untapped hydropower potential is finally becoming a tool of socio-economic development and not just a source of psychological satisfaction.

|